Dude! Take Your Turn!

A Gaming Life

Defiance or Appeasement? – Bell of Treason Review

There’s something about a meaty game that plays in 45 minutes that just appeals to me.

It makes for a nice lunch but it still exercises the brain a bit.

Adding historical flavour is just the icing on the cake.

I really enjoyed Mark Herman’s Fort Sumter back in the day, though I never did actually get around to reviewing the next game in “Final Crisis” series.

Today, that changes!

The latest in the series, The Bell of Treason: 1938 Munich Crisis in Czechoslovakia, was just released (in 2025 for those of you reading in the future) by GMT Games.

(And from now on, it’s just Bell of Treason).

The game was designed by first-time designer Petr Mojžíš with graphics by Tomasz Niedzinski and plays 1-2 players.

(Note: I haven’t tried the solo game yet)

The system has evolved through a couple of games now and I’m liking the changes.

The concept behind this game is that there were two sides to the whole Czechoslovakia crisis in 1938: the faction that wanted to “defend” Czech sovereignty against German aggression, and the faction that wanted to “concede” to German demands regarding annexing the Sudetenland.

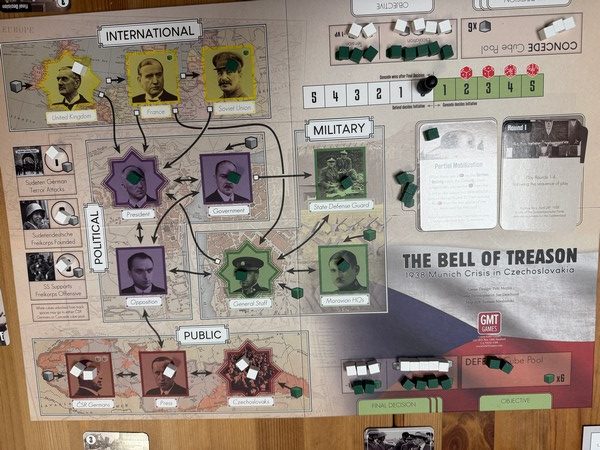

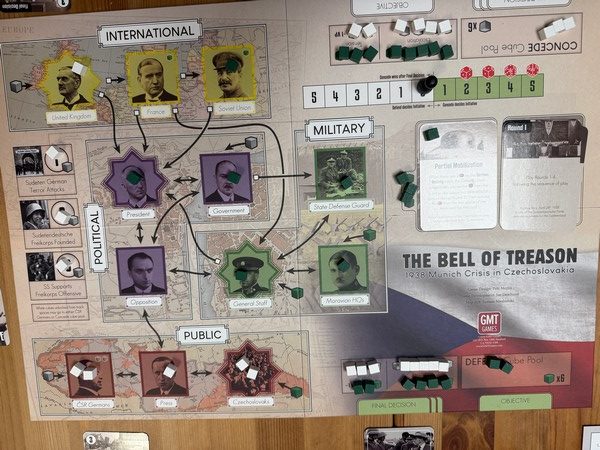

The major part of the “Final Crisis” game system is the use of four different “crisis dimensions”, which both players vie for control of to try and score victory points.

“Pivotal” spaces are the 8-pointed star shapes while the other two spaces in each dimension are square.

Control of Pivotal spaces at the end of the round will let you do one action in that dimension, which perhaps will give control of the dimension to you, if you end up controlling all three (“control” just means you have more cubes there than your opponent)

Unlike previous games in the system (though Red Flag Over Paris already began this a little bit), the “adjacency” arrows for the various spaces really reflect the historical flavour of the Munich crisis.

The adjacency arrows in Bell of Treason make playing cards and placing cubes really interesting.

Regarding the International dimension (the yellow one at the top of the board), the United Kingdom is adjacent to France and France is adjacent to the Soviet Union.

But not vice versa!

If you control the Soviet Union, you can’t place cubes in the other International areas since the arrows are one-way.

The International crisis dimension as well as the General Staff space of the Military dimension (as well as both other Political areas) can influence the President.

The only Public area that’s adjacent to a Political area (and that’s only the Opposition) is the Press.

It’s all quite intricate!

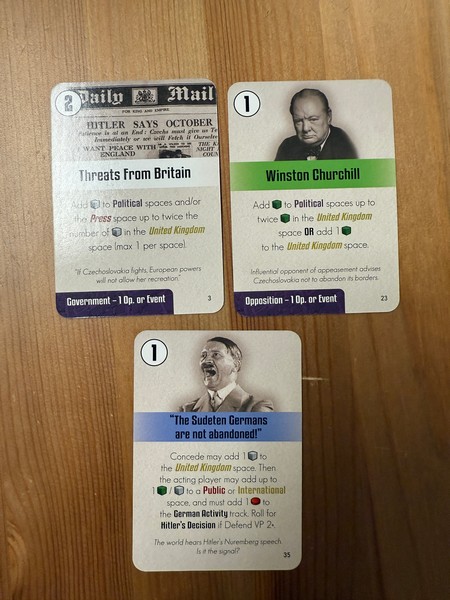

Meanwhile, each player is playing cards (just like any Card-Driven Game) where they can use the Operation points in the top left corner to place friendly cubes or remove enemy cubes, or they can do the Event if it’s theirs (green for Defend, white for Concede, and blue for “either”).

Another aspect of the game, which was an optional rule in Fort Sumter but became normal in Red Flag Over Paris (and another lunchtime game, Flashpoint: South China Sea), is the ability to discard a card of equal or higher Ops value to play your own event (or a blue event) that the other player played for Ops.

This can lead to some interesting decisions.

When should I play this card that I’m stuck with that might help my opponent?

Maybe I should wait to see if they use their higher-value cards beforehand?

These types of decisions are what makes Bell of Treason so interesting, even compared to the early versions of the system where you didn’t have quite as much to consider.

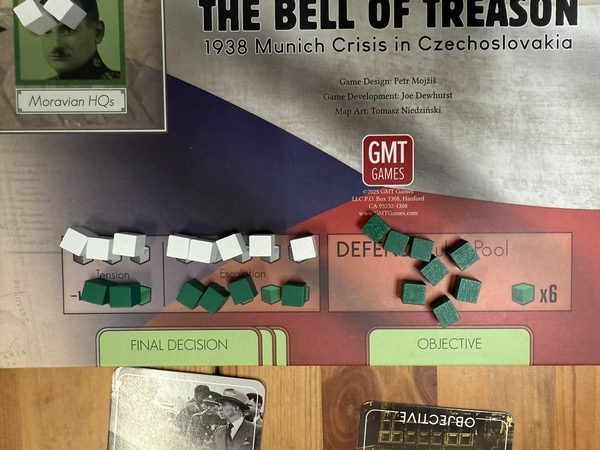

Like the previous games, there are zones that you can breach to give yourself more cubes.

If you breach the “Tension” zone, you lose 1 VP.

The interesting aspect of this from Bell of Treason is that doing this will actually give your opponent more cubes than it will give you!

You may still need those cubes because you are out of them and your opponent hasn’t been placing them as fast as you have.

But it’s a consideration.

The opposite is true of your opponent: if they breach, they give you more cubes.

But if you breach first, they have more cubes to deal with before they even need to consider breaching.

But maybe you need those cubes!

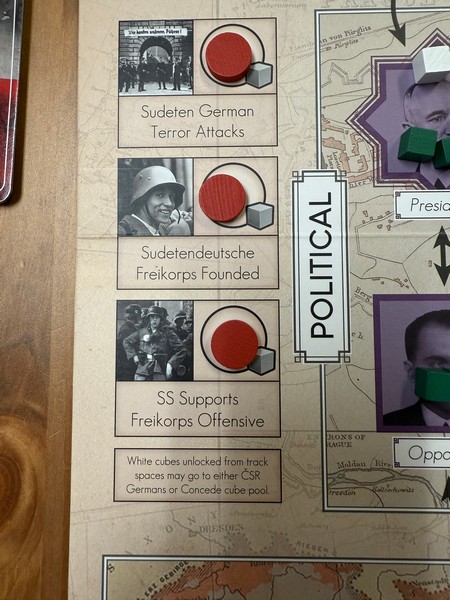

New additions to this game compared to previous ones have great historical effect from the Munich crisis.

There is a track that keeps track of German incursions, and which as red discs are added to it, the Concede faction will get more cubes to use.

This represents the German strength and helps the Concede faction because they want to concede to German demands.

The “Defend” faction has their own version of this, regarding mobilization of the Czech armed forces.

Defend wants to get the military going to defend the country against German incursions.

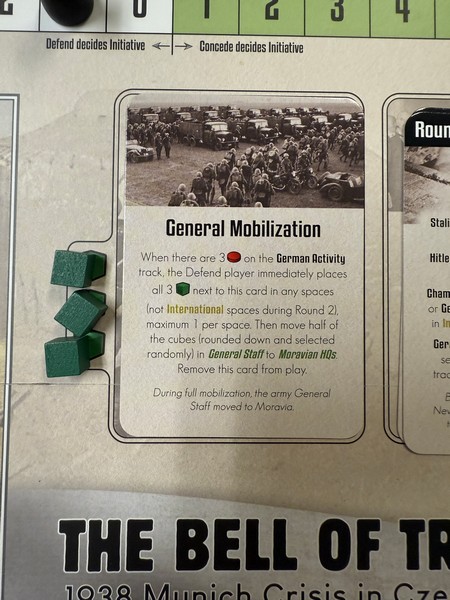

When two red discs are put on the German track, Partial Mobilization happens.

This can be done by an Event played, or one disc is added at the beginning of each of the 2nd and 3rd (Final) rounds of the game.

When Partial Mobilization happens, the Defend player gets one cube that they can put anywhere (though if it happens in Round 2, they can’t put it in International spaces).

When three discs are on the track (which does require an Event to be played, as the rounds will end up just with two discs placed), General Mobilization occurs and the Defend player gets three cubes to put out anywhere (with the same 2nd round restriction as the Partial one)

Compared to the other games in this series, I love the push-pull aspect of this mobilization vs conceding to the Germans, as well as the fact that breaching areas to get cubes will actually give your opponent more cubes than it will you.

The General Mobilization will also randomly move around cubes in the Military dimension which, if it’s being contested by both players (unlike our third game of this), can have big consequences.

There is also always the chance, if the Defend player is getting victory points at Concede’s expense, that the game will end due to Hitler just deciding to invade.

At the end of each round, if the Defend player has 2 or more VP, then you roll a die.

If the die is equal to or more than the Defend VP, then the game ends with a Defend victory.

It is also theoretically possible that both sides will lose, if Hitler invades before the Czech military is fully mobilized (meaning Partial Mobilization hasn’t happened yet but Defend still has high VP and the dice roll determines that the game ends).

These extra aspects of the game really make the game shine, even compared to the previous ones.

The victory conditions are also really interesting and make the Defend player have to make sure they’re controlling the right areas.

If the Defend faction has the most VP at the end of the game, they still have to consider the President space (since he was instrumental in the crisis).

Defend has to have more cubes in the President space plus cubes in spaces adjacent to the President, then Concede has in the President space.

This should be relatively easy to do, but maybe not!

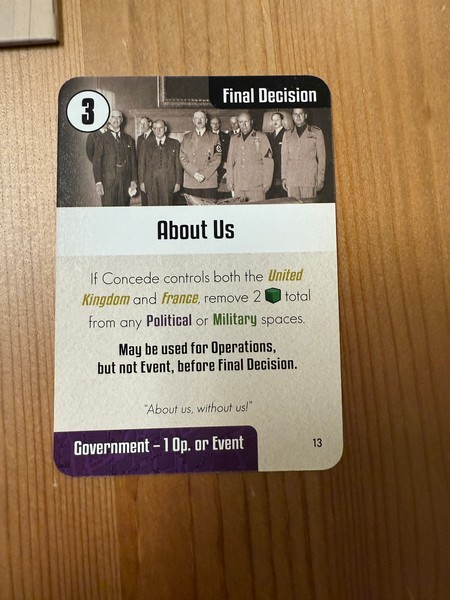

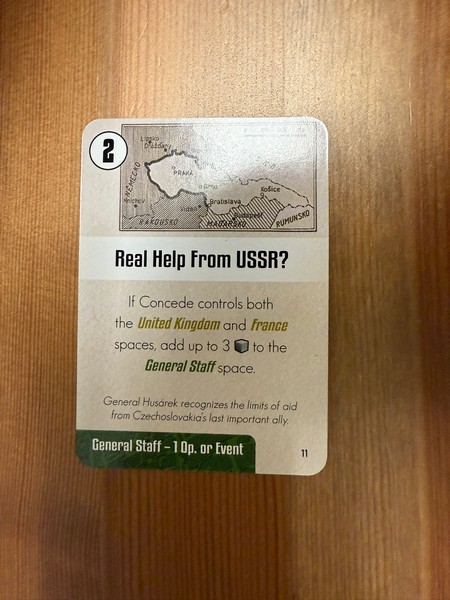

As usual with these games, at the end of each round, you will have played four cards for either Ops or the Event (or discarded a card to use the discarded Event) and the fifth will be placed in the “Final Decision” area. (In previous games, this was “Final Crisis”)

Red Flag Over Paris added a Final Crisis card for each faction that can be used for Ops points during the game, but if not used can be used for the Final Crisis.

Bell of Treason carries forward that tradition. Assuming you haven’t already used it, you take the three cards you saved during each round and then discard one of the cards (or the Final Decision card).

After three rounds, you do the Final Decision round, where you take your three cards and reveal them one at a time.

These cards only look at the crisis dimension space showing in the bottom left (or some cards will actually let you use the Event as well).

In something that I’m not used to taking into account, which card you save for the Final Decision does not matter in regards to whose event it is (like 13 Days).

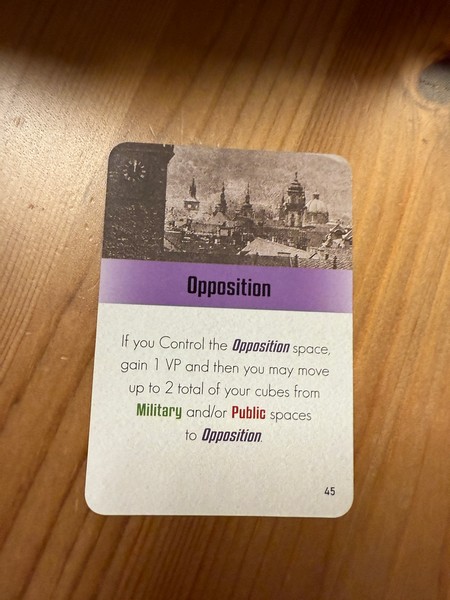

In the above card, all you care about is the green “General Staff” part at the bottom.

You reveal them one at a time with your opponent.

If the area matches (say “General Staff”, like above), then nothing happens.

If they don’t match, then each player will get to use 1 OP in that specific space (or some will let you do the Event, like the above card).

Finally, you score the Political and Military dimensions one more time to determine the final score.

The Final Crisis system of games is kind of abstract, but increasingly the game board adds to the historical value of the game.

Fort Sumter just had areas adjacent to each other without really differentiating them.

Beginning with Red Flag Over Paris, and even more so with Bell of Treason, the adjacencies actually have historical context, which I really love about this game.

Also, I really enjoy the push and pull regarding Czech mobilization and the German readiness to invade.

I think this is the first game where both sides can lose if things go tits up early in the game.

I love that!

Though it does make recording the game on BG Stats a bit harder.

Another change that I really love compared to the other games is the fact that breaching zones for more cubes actually helps your opponent more than yourself.

All in all, I just felt more like I was in the middle of a crisis than I have in the previous games (though Red Flag did have that as well).

Concede gets some benefits from the Germans encroaching further, but the Defend faction gets even more because it enables Mobilization and gets them cubes.

I’m still not sure what the best strategy is, because I lost my first two games by not getting enough cubes on the board.

In the third game (as Concede), I flooded the board with cubes. So much so that I actually didn’t have cubes to place when some events let me place them (you can’t move cubes around once they’re placed, unless something specifically lets you do that), and the Defend faction had plenty of cubes to place before they needed to breach.

If my opponent hadn’t made a couple of mistakes, I may have lost due to the inflexibility of my situation.

The card play is really interesting, especially the addition of cards that are reshuffled back into the deck (though we kept forgetting to do that!) which means some cards may be seen more than once.

Like the other two games, each player will get an Objective card each round which can give them a VP and an event if they manage to control that space.

You have to make sure you can control that space because it can put you behind if you don’t.

Bell of Treason is kind of susceptible to the “runaway leader” problem, at least in some respects, unless you manage to get an event that will change everything.

If you mess up an Objective or let your opponent control a couple of crisis dimensions, then you’re screwed.

As long as you are aware of that possibility, Bell of Treason is a wonderful game.

It plays in 30-45 minutes, which means you can play it a couple of times and switch sides.

As a first-time designer, Petr Mojžíš has hit it out of the park.

This is the rare abstract game where you kind of feel like you are at the center of the thematic action.

The cards are historical events (the Playbook details the history behind each card), the Munich crisis is an area that hasn’t really been covered by games so it’s fresh, and the design just seems to take the best of both previous games and meld them into a really gripping game.

It’s hard to find another 45 minutes that’s historical yet also just plain fun.

(This review was written after 3 plays)

I played an early version of it at SDHistCon (online) once and very much enjoyed it! I’m glad the finished game has turned out so good – and that it fills this niche of substantial history game in a relatively short playtime!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Any changes that you noticed from my description? It’s so cool you played it early!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Nothing that I noticed… the game looked pretty ready visually as well. I guess there was still some fine-tuning on the event cards to do to ensure balance.

A very timely game, too – Czechoslovakia conceded back then, and many observers expected Ukraine to back down (or simply collapse) under Russian pressure… but in our time, the “Defend” posture has prevailed… so far.

LikeLiked by 1 person