Dude! Take Your Turn!

A Gaming Life

Putting Wood on the Biblical Fire

Reading the description of Ezra & Nehemiah when it first hit Kickstarter, I was intrigued.

If you read this blog for more than just one or two posts, you know I’m a huge fan of Garphill Games and the games designed by Shem Phillips and SJ MacDonald.

While I have enjoyed pretty much every “trilogy” game, I haven’t played many of their other games, including any of the “Ancients” line of games (which aren’t connected at all, except that they all portray “ancient” history in some way).

This was apparently going to be their heaviest game yet, and the setting of the game was also very attractive.

The game takes place in the aftermath of the Babylonian Captivity when the Judeans were returning to Jerusalem and having to rebuild it.

The temple was destroyed, all of the city walls and gates were nothing but rubble.

You, as players, have to take on this daunting task of rebuilding, as well as installing new scholars and teaching the Torah to the masses.

The game actually condenses these years of activity into three weeks (I wish our downtown skyscrapers would get built that fast!), one of many aspects of the theme that seem a little out of place.

I admit that I know very little about the Babylonian Captivity, nor do I know much about the rebuilding of the city.

My friend Dan Thurot over at Space-Biff has done a very good review that talks a great deal about the thematic disconnects he found in the game.

But how does it work as just a game, especially if the issues with the theme don’t bother you?

Ezra & Nehemiah is a game where almost everything you do will get you something, not just for the future, but for now.

Burn stuff on the altar? Not only do you move up on the altar track, but almost every step you move will give you something. This could be a blessing, or maybe some gold, or some money or food.

Build in the temple? Unless you are the least pious person ever working in the temple, you’re going to get something else as well as the points.

The only time this doesn’t happen is when you place your scribes, and the future benefits you get from that are so great that getting anything else would be overpowered (and even then, you might get some food or even a point).

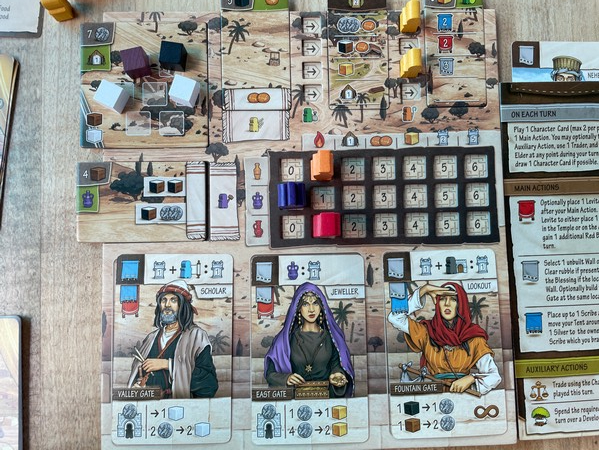

As with most games designed by this illustrious duo, there are three areas in the game were you can spread your actions, or concentrate on one or two and totally ignore the third.

The most basic one is rebuilding the city walls and gates, and this is where you are going to be getting a large portion of the resources you need to do other things.

It’s reasonably cheap, not costing any money and the resources it costs were probably obtained from your previous excavations anyway.

If you actually build a wall, you will get endgame points and also some other benefit.

The temple-specific aspects are a bit different.

First, you can always pay some food to put one of your workers into the temple as a Levite.

These Levites will grant you actions in the temple or, if you don’t want to do that many actions, can also add strength to the actions you do want to take.

Even better is that you don’t have to feed them at the end of the week!

Yes, yes, for some reason, they have now added one of my least-favourite features to Ezra & Nehemiah: feeding your people at the end of a round.

I really hate that mechanism, though it’s not too bad in this game. Instead of just automatically causing you to hemorrhage points at the end of the round, the worst it will do is make you have to divert your strategy during the round a bit in order to make sure you have enough food.

Sometimes it’s more lucrative to get a bunch of points through actions and then lose 2 VP each for a couple of unfed workers.

Unused workers actually will go to the fields and end up feeding themselves too (or, if you already have enough food, you can send them to the mines to get you resources instead).

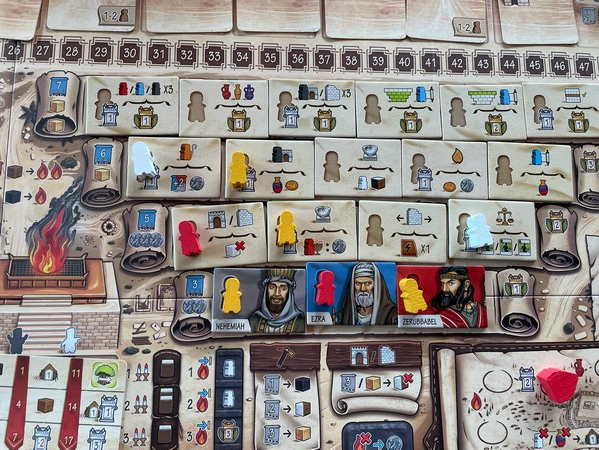

The third track is a blue track, where you are hiring your workers to become scholars, and also moving around the city to teach the Torah to the common people who have come back to the city but still need to be educated.

The scribes are the only place where you won’t get something (most of the time) for putting a worker there. But their effects are so great that it won’t matter, because they will get you a bunch of benefits during the rest of the game.

This can be anything from “you don’t have to feed your scribes” (which is huge if you are going for a scribe-heavy strategy) to “pay 2 less food when placing a Levite” to “gain a blessing when you place a scribe.”

While it can pay off to not go heavily into scribes, some scribes will help you with one of the other tracks as well. I had a scribe that let me pay cinders for building walls. That’s huge considering that all walls require wood and stone (building walls with cinders seems…counter-productive)

I’m not sure thematically how that makes sense, but what the hell?

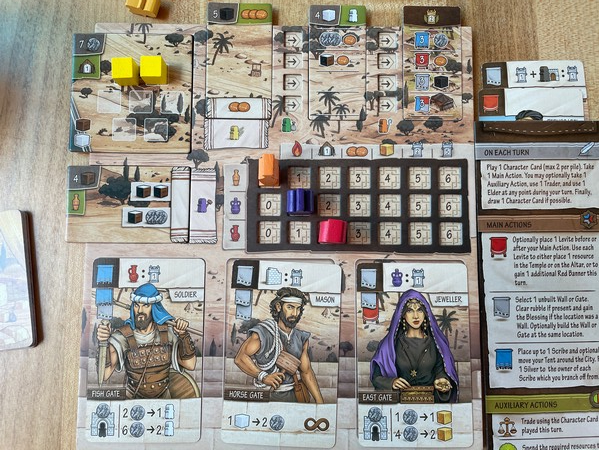

All of this is done in a neat variation of the Paladins of the West Kingdom banner mechanism when playing Paladins and taking action.

Each turn you’ll be playing a card from your hand with banners.

When you play a card, you can take a main action that will use either the grey (walls/gates), red (temple/altar) or blue (scholars/Torah) banners.

The actions you take will cost a certain number of banners and you will spend them (unlike Paladins where you just have to have enough) in order to do the actions.

Burning cinders on the altar costs 1 red banner. Burning wood on the altar costs 3 red banners. Placing stone/wood/gold in the temple costs red banners depending on the level (I guess how devout you are?).

Moving around the city costs blue banners depending on how far you want to move.

As I mentioned above, with every action basically getting you something, moving around the city teaching the Torah gets you benefits for each move.

Moving multiple steps by spending a lot of blue banners will get you a bunch of stuff.

Maybe a purple blessing, maybe a new worker, or some food.

Also, hiring a new scribe costs blue banners, as well as money or gold depending on how prestigious the scholar will be.

Once players have played 6 cards (taken 6 turns), the Sabbath happens.

Some scribes or other effects will get you some benefit, and then you resolve the altar.

Then you have to feed! I hope you kept enough food.

There is one really interesting decision that the Sabbath forces you to make.

At Sabbath, you will have played 6 cards to your board.

You have to choose one played card (two during the second Sabbath) to tuck and score.

These cards will score on this Sabbath and any subsequent Sabbath, and they will also give you a free banner (the top banner on the card).

The Soldier above will get you one point for every Red blessing you have.

However, these cards are now out of your deck for the rest of the game.

You will no longer be able to use the Soldier for its two Blue banners and one Grey.

This is where you need to decide whether you’re going to need that card later (played cards that aren’t tucked will be shuffled into a new draw deck) or whether the points it gives you are worth nuking it forever.

To me, that is almost an agonizing decision. If you have two scribes in high positions early, you can tuck the card that lets you score your highest scribes early and get a ton of points!

But then you don’t have access to the card that gives you three Blue banners anymore.

That push and pull is really cool for me and one reason I like this game.

That being said, there is something keeping me from really loving this game.

Dan does talk a lot about the thematic disconnects, and it is a fascinating read so I hope you do read it.

But even for somebody who doesn’t know the history, some of the thematic aspects just jar a bit.

Yes, I realize that they had to condense years of work into three rounds so that the game doesn’t go over 50 rounds.

But condensing years of work into a week just feels funny.

I managed to completely clear two sections of rubble and build two walls in a whole week!

Something that really would take weeks to do and a lot of manpower.

I guess that’s what the grey banners represent? Manpower?

One could say that abstracting the years of work (on whichever track) into three weeks almost abstracts the work involved into oblivion.

Also, what are players supposed to be in this game?

Something Dan also touches on in his review.

In the trilogy Garphill games I’m familiar with, players are the architects who want to build the most prestigious part of the city in the West Kingdom, or maybe the person who explores the Mediterranean the best, or who heads the most prestigious translation guild out there.

Here, though?

You’re all trying to rebuild Jerusalem and revive Judean religious studies, rebuilding the temple and giving your people a place to worship, something the Judeans need in order to survive and revive their culture after years of captivity.

But what are you fighting for against the other players?

Points, I know.

But what else?

Let me quote Dan’s review for a moment:

“But this emphasis on the passage of time and a national Sabbath makes the game’s omissions all the more apparent. It isn’t only that the history of the early Second Temple Period is simplified; it’s unthinkable that it wouldn’t be. Rather, it’s that the complexities have been reduced to such a degree that one begins to suspect that certain details have been willfully omitted for the sake of making the story glint a little more brightly.”

Disregarding for the moment all the points Dan makes about omission and the religious aspects that he finds lacking in the game, what are we doing?

I don’t know, really.

I know we’re rebuilding the city and educating the masses, but I don’t know why I’m competing with my opponents in doing so.

Some might say the theme in the other games is pasted on and you don’t really feel like you are doing what ostensibly you should be doing.

I don’t agree, but I can understand that point.

But in Ezra & Nehemiah, I totally get that point.

Not that the theme is pasted on. I don’t agree with that.

I just don’t think the theme works as a mechanism like it does in the other games.

As a game, I do like some of the mechanisms.

You are at the mercy of your card deck as far as the banners that come out.

When you play a card, you also use the banners that are still visible on your player board in order to do the action.

That’s a really cool thing.

Once you have three cards out and the next card has to be played on top of one of your others, it can be hard to decide which one to cover up.

Their banners are no longer useable.

It requires some forethought, but then again, until the last round, you don’t know what cards you will be getting when you have to make that decision.

You can also use some of your workers as merchants or elders in order to get banners or resources that you need.

Any workers that you haven’t used at Sabbath can be sent to the fields (for food) or the mines (for resources), as if they’d been there all week.

Which is a bit weird, but whatever.

It’s like gaining food or resources doesn’t need to be planned at all.

Ultimately, Ezra & Nehemiah has some really cool mechanisms, some that are adapted from previous games (like the banners, though spending them rather than just having them, or the connection bonuses when building next to a gate that are similar to the building bonuses in Viscounts of the West Kingdom).

I wouldn’t say that the game is derivative at all, as these mechanisms are used in unique ways that are enjoyable.

It’s definitely the most complex Garphill game out there, as far as strategy goes, anyway.

Like most of the Garphill games, the strategy is definitely more complicated than the actual mechanisms.

And this is a game that I actually played correctly from the get-go with no rules mistakes!

Other than, for some reason in our third play, I forgot that you have 4 cards in your hand, not 3.

I really like Ezra & Nehemiah as a game. It’s fun, it burns my brain in just the right way.

But it’s just never going to reach the heights of the other games in my opinion. Whether it’s because of the thematic issues or because I just don’t love how the mechanisms go together, I’m not sure.

It does seem very mechanical at some points, almost to its detriment.

I would definitely suggest trying this one, unless you have enough biblical knowledge that many of the issues Dan mentions may get to you too much for you to enjoy it.

But if you have tried other Garphill games and bounced off of them, this one isn’t going to change your mind.

(This review was written after 4 plays)